A Brief History of Showpigs

“…when it is a question of pigs, those boars must meet with our approval which are remarkable for their outstanding bodily size in general, provided that they are square rather than long or round, and which have a belly which hangs down, huge haunches, but not correspondingly long legs and hoofs, a long and glandulous neck, and a snout which is short and snub…”

- Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella (4 AD - 70 AD), De Re Rustica

Why do we show pigs? Who decided to take the humble swine, resident of muddy farm backyards and recipient of kitchen waste, and turn them into an animal that is treated more like a prize racehorse than a source of bacon? This article seeks to answer that very question, and it is a more complicated one than you might think.

Sacrificial Swine

Suovetaurilla

A Roman sacrifice of a pig, cow and goat to the god Mars.

The first cases of animals being “exhibited” for their characteristics are actually from the ancient Mesopotamians, over 5000 years ago, for the purpose of animal sacrifice. Clay tablets from Uruk have lists of pigs, divided into those fit for temple sacrifice, sows, boars, and others. The priests would inspect the skin for blemishes, ensure these pigs were healthy, and ensure they were “good-looking”. Several thousand years later, the Greeks also had this practice in their religions, and similar evaluations of fitness took place. In 300 BC, the Greek playwright Aristophanes records women publicly inspecting pigs in agricultural festivals such as the Thesmophoria and Eleusinian Mysteries, where sows were ritually displayed and sacrificed. The Romans were much the same until their Christianization, with Suovetaurilia being an important ritual for Roman military leaders. However, the Romans also give us the first glimpse of the type of evaluation we would one day recognize in the show ring, and our record largely starts and ends with two men. Columella, the man quoted above, of which little is known besides the work quoted. And another, far more revered Roman by the name of Marcus Terentius Varro.

From Varro to the Middle Ages

Marcus Terentius Varro (116 BC - 27 BC)

Widely considered the greatest Roman scholar, Varro was a military leader, scientist, philospher, linguist, historian and poet.

Varro was a genius beyond compare. He led armies under Pompey, theorized about disease-causing microorganisms two millennia before Louis Pasteur, wrote on the origins of Latin, and completed over 620 books across 74 works. He also wrote a guide to all things agriculture in his work, commonly titled “De Re Rustica”, the same title as Columella’s work on the topic. In it, he talks about selecting boars for their broad shoulders, heavy bones, and other notable characteristics we still hear discussed in the show ring today. Varro and Columella were some of the only sources we have until the early Medieval period that spoke on this topic. Fast forward to around 800 AD, the Capitularies of Charlemagne, part of the Carolingian Reforms, stated that swine must be brought before the inspector and evaluated for thier quality. Another two centuries closer to us in the 1000s, the people of what would be the British Isles began to hold annual folkmoots and michelsceat fairs where livestock, including pigs, were traded and weighed in public view. Domesday Book (1086) records pigs by quality categories (“tame,” “wild,” “improved”) for taxation, implying a certain standard of evaluation. These folksmoots are the orgins of the county fairs we have today, and here is where the fun truly begins.

Medieval England to the Modern Day

We finally have FAIRS! The staple of hog shows across the nation, and we have arrived at their origins. From around 1250-1600, sources like the chronicler Matthew Paris note things like this:

“At the fair of Saint Albans, many from various parts came with pigs, sheep, oxen, and other animals; prizes were given to those who presented the finest animals.”

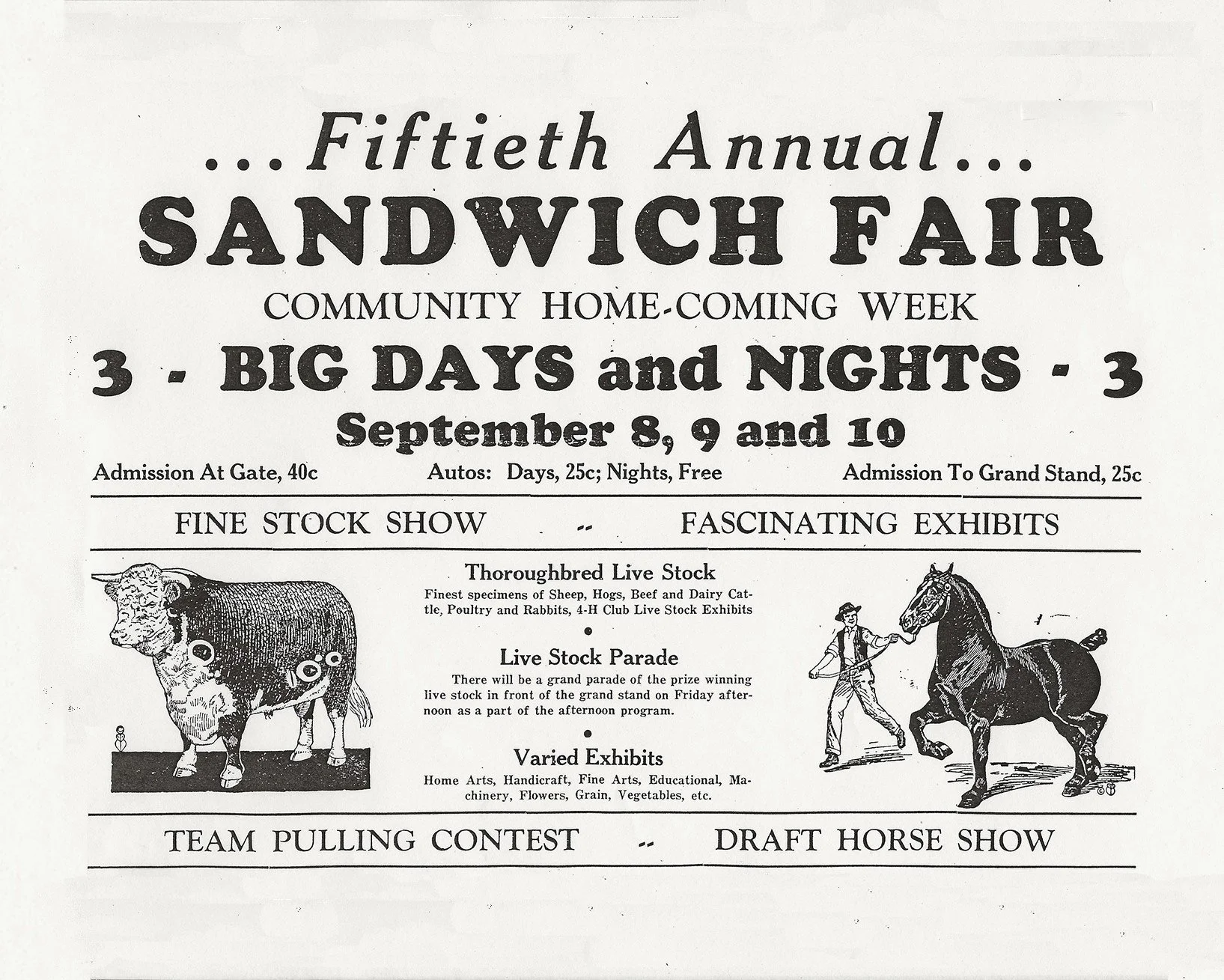

Perhaps even blue ribbons were given out, who knows? These fairs, especially in England, coincided with the development of distinct breeds and the beginning of standardized selection by men like Robert Bakewell, who held “proto-shows” with his public viewings at Dishley Grange in the 18th century. County agricultural societies institutionalised these viewings: the Bath and West Society (1777) and Smithfield Club (1798) offered cash prizes for “the best fat hog”, and by the 19th century, publications like The Farmers Magazine in London were reporting things like this: “Short-legged Berkshires and white pigs of the improved Yorkshire type, exhibited to great applause.” These practices and association types were imported to America, and by the 1850s, nearly every State Fair had hog shows of its own, even divided by breeds, whose registries were slowly emerging, with the likes of the Poland China, the Chester White, and the Berkshire associations being created in the 1870s/1880s. Shows we know today, like the International Livestock Expo and the National Barrow Show, began in the 1920s. The creation of 4-H and FFA around the same time got hundreds of thousands of youth organized and involved with agriculture, massively boosting the creation of youth swine shows around the country. From there, things have certainly changed, but the core idea of kids bringing kids into the ring for a judge to evaluate is the same today as it was in 1925. The true “showpig" industry itself did not diverge greatly from regular hogs until the 1980s/1990s, but that is most definitely a topic of its own.

The Past is a Foreign Country

Now that our journey through time has arrived in the present, it may seem like this industry of ours is truly strange in its origins. It is truly remarkable that we derived our well-broke showmanship partners, our backdrop-hitting barrows, and our pampered show gilts from the practice of pagan animal sacrifice and a Roman polymath's interest in making tastier bacon. However, I hope that this little trip down humanity's collective memory lane serves as an exercise in seeing how our civilizational ancestors were massively different in their ways, customs, practices, and beliefs, and how our current civilization is in many ways absolutely and without question unique. Also, I think I will end this monologue with a quote from our dear friend Varro.

“Homo memoria tenet, litteris tradit, monumentis mandat; ita per culturam humanitas servatur.”

“Man holds things in memory, transmits them by writing, entrusts them to monuments; thus through cultivation, humanity is preserved.”